Ray-Marched Voxel Simulation

I have created a new voxel engine that is designed to handle fully dynamic scenes. Inspired by classic falling sand games, my aim was to create a system that can handle many unique interactions between different materials. The world is rendered using direct voxel volume rendering, such that changes to the world are immediately reflected on screen. As we are updating upwards of hundreds of millions of voxels, many times per second, the entire simulation is run on the GPU using compute shaders.

Today I will go over how I render the world, how I manipulate the voxel data and finally some minor additions such as simple collisions and shading.

Basic Voxel Ray Marching

But first, what are voxels? Unlike popular belief, they a re not just cubes, but rather simply data points on a regularly-spaced three-dimensional grid. By sampling voxels using nearest neighbour interpolation, we do end up with the familiar cubical structure, which is what I will use for this project. I use a storage buffer with 32 bits per voxel. Each voxel stores its type in 8 bits, its color in 16 bits, and it has 8 bits for auxiliary data. Each voxel is scaled down such that its edges are one eight units in length for more detail.

To render the voxel data, I use ray marching. Unlike with signed distance fields, we do not know the distance to the surface. Instead, we can naively take equidistant steps throughout the voxel field. However, this way, we either wastefully sample a voxel more than once, or we risk stepping through a voxel, and thus missing an intersection.

A more thorough approach is the Amanatides and Woo algorithm [1]. The idea is that we compute the distances to the three upcoming grid aligned planes, and step the ray with distance to the closest plane. Based on which plane we intersect, we simply take an integer step in the voxel grid in this direction. As the voxel grid is uniform, we can precompute these distances and deltas before stepping through the grid. We can make it even more efficient by using a mask instead of if statements, to reduce thread divergence when executing it on the GPU.

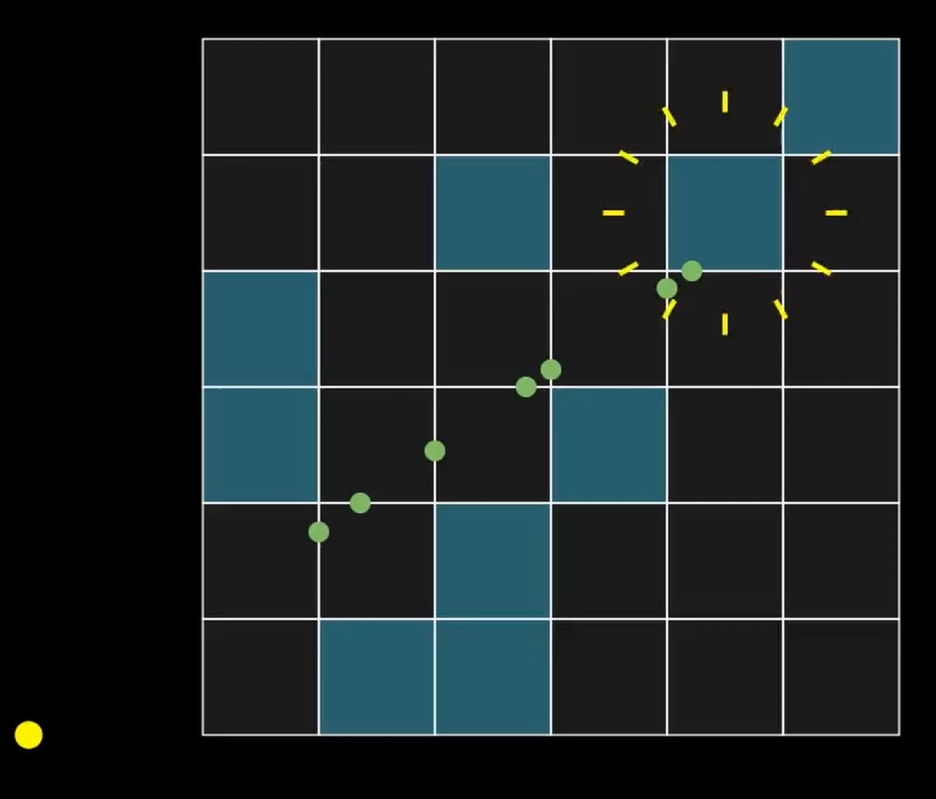

Voxel Bricks

While this algorithm is fast, large voxel worlds slow it down. The most common way to improve performance is using a hierarchical structure. As I want to prioritize interactivity, voxels may change a lot, and thus the structure overhead must be minimal. I have therefore chosen for the brickmap approach [2]. We group voxels in bricks of size 8 cubed. If all voxels within a brick are labelled as air, we mark the brickmap as empty. During the ray marching step, we first check if a brick is empty. If so, we know we can safely move on to the next brick, otherwise we perform the algorithm discussed prior to traverse all the voxels within this brick.

This drastically improves render times, primarily stemming from the great reduction of steps each ray has to take. In the future, I would like to further expand on this approach by only allocating enough voxel memory for all the occupied bricks, and dynamically allocating more when the simulation demands it.

Voxel Edits

Now that we have the ability to render the world, we can make it interactive. I let the player edit the world using a raycast. First, in a really simple compute shader, I compute the ray intersection with the world. While it is a bit wasteful to use a single GPU thread for this, it beats having to move all the voxel data to the CPU first. This shader writes the result of the raycast to a small storage buffer that is used by a second shader. Around the found position, I place a ball of voxels, based on the selected material. Since this is all handled on the GPU, without being constricted by much data structure overhead or a surface extraction algorithm, there is virtually no limit to the amount of voxels that can be edited, other than the world boundary.

Simulation

The GPU also enables us to run a simulation the size of the entire voxel world with many steps per second. To achieve it, I borrow concepts from cellular automata. Cellular automata is a model of computation often used in computer graphics that involves changing values in discrete cells based on the values of their neighbors. A famous example of this is Conway’s game of life, in which each cell is either turned on or off based on the number of active cells around it. We can expand this concept to facilitate something that resembles water.

First, water is affected by gravity. We check if a spot underneath the voxel is filled with air, and if so, we move it there. If not, we will want to move the water sideways. By computing a combined hash of the position and the current frame number, we get an adequate pseudo-random number generator, which we will use to move the water in an arbitrary axis aligned direction. Once again, only if the voxel in that direction is not occupied by anything solid.

As this direction is randomly chosen every frame, water voxels tend to wander around, which is not what I had in mind. To fix this, I store the first horizontal direction it successfully moves in, and I will keep moving it in this direction until it hits a wall, at which point it randomly selects a new direction. I do give it a small probability to go to the side, as this makes it look slightly more natural.

For lava voxels, I run the exact same code. Except now, in a second pass, we check the von Neumann neighborhood of each lava voxel for water. If we find any, we turn the lava into stone.

Sand is also quite similar, but it should not keep moving horizontally. Instead, It only has the ability to fall down directly, or if obstructed, fall down diagonally. These simple rules result in sand that piles up in pyramid shapes, rather than in whatever shape it was initialized as. Sand also pushes up liquids it falls onto.

Algorithm Correctness

However, we cannot just write to the neighboring voxels without any issues. As we process this on the GPU, many voxels are processed at the same time, so we will run into concurrency problems. To ensure correctness, I use two buffers. One buffer corresponds to the data from the current time step, and one for the next time step. Once we have finished a computation iteration, the previous buffer can be cleared, and used for the following time step. This is often referred to as ping-ponging, as we constantly swap the reference to the latest buffer between buffer one and two. The benefit of this is that every thread consistently uses the same information to compute its next state, untainted by changes already made to neighboring voxels.

This alone is not enough. Currently, two threads can both write to the same voxel, leading to the possibility of voxels disappearing. This can be fixed in multiple ways. For instance, we can use multiple passes, where every pass only moves voxels towards exactly one direction.

As this over complicates the implementation, I instead make use of the atomic compare-and-swap operator. It takes a pointer to the data we want to write to, a value of what we assume it should be before writing to it, and a value we want to write to it. It will only perform the write operation if the actual data stored at the pointer is the same as the assumed data. If it differs, no write operation will be executed. Regardless, it returns the value it found before writing. By comparing that to our assumed value, we can gauge if the write operation was successful. Atomic operations can reduce the performance, but so far I have not had any issues with it in this context.

Because of both edits made by the player, and the cellular automata, the voxel world can change greatly. This is a problem for our brick based approach, as it loses track of which bricks are occupied. So, we recompute brick occupancy in another compute shader. Per brick, I start a thread block with exactly 32 threads, each read the values of 16 voxels within their own part of the brick. They count the number of those voxels that are not air, and write it to their own unsigned integer in an array in shared memory. Then, we sync all threads within the block. Finally, the first thread in the block sums the values stored in shared memory, and writes it to the voxel brick. This is fast, as we don’t require any atomic operations, and shared memory is faster than global memory.

Collisions

If we want the world to be interactable, we want the player to be able to stand on solid voxels. I want to use Godot’s physics system directly, so I will build a convex collision mesh. To this end, I incorporate a small surface extraction step, localized around the player.

First, we asynchronously collect all voxel data around the player. As we only care about a voxel being solid or not, we store this in a single bit per voxel. Once we have the data on the CPU, we build the mesh. We do this using a very simple culling algorithm that generates a single quad for every face in the voxel grid that separates the solid from non solid data. I rebuild this collider only a couple times per second, which is good enough to handle normal player movement.

Visual

Finally, let’s add some visual flair to the world.

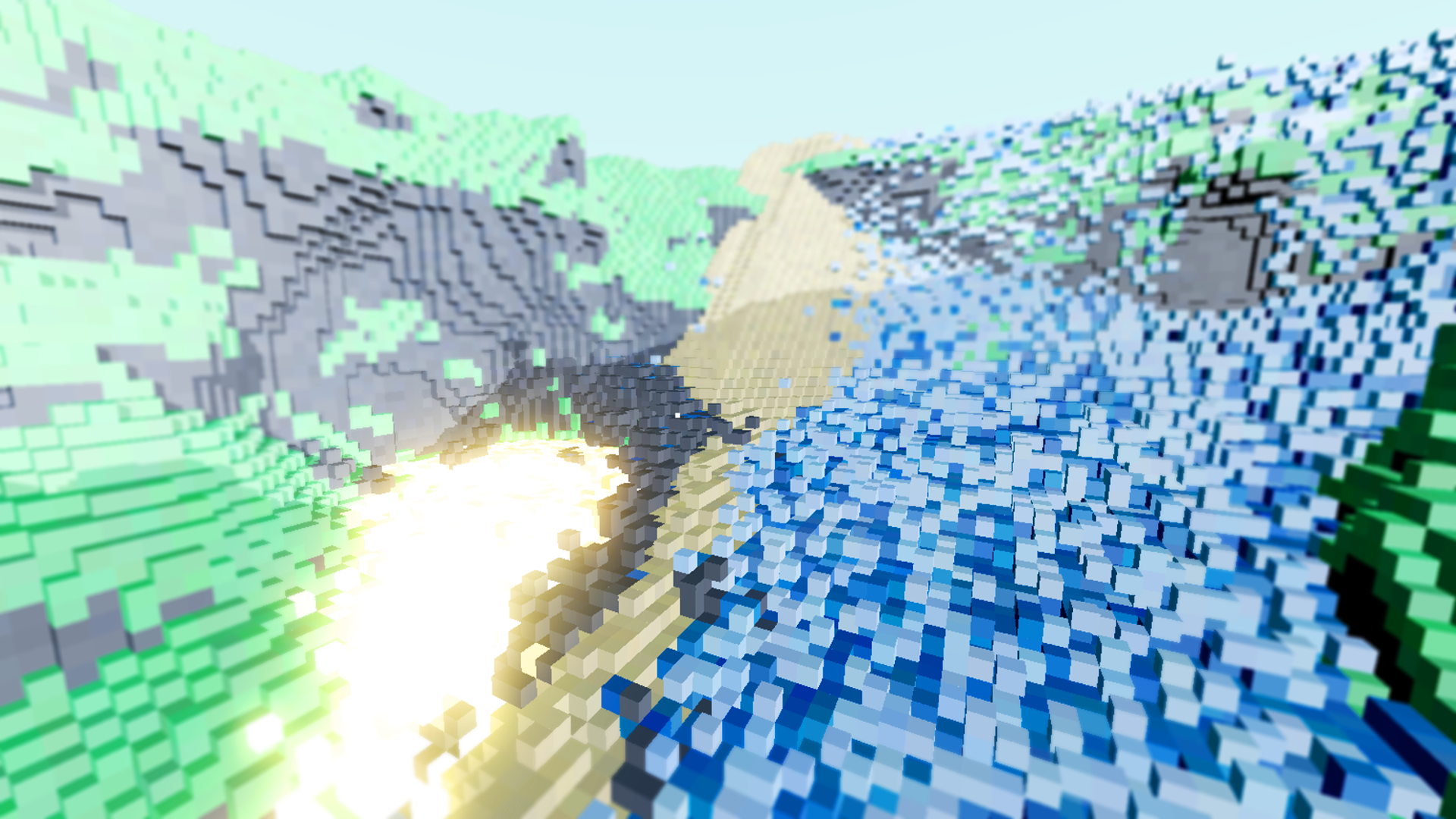

First, using basic hashes and fractal noise, we can generate a simple terrain. For this project, my goal is not an infinite world, so we can generate the full thing in one go. After creating a basic shape, we set the voxel to grass if it has air two blocks above it, or rock otherwise.

I also added simple blinn phong shading. By rounding the camera ray hit position to the voxel grid, we obtain per voxel specular highlights that fit quite well. Additionally, by firing a secondary ray towards the sun, we get simple hard shadows based on if this ray was occluded or not. I also added a simple skybox with a sun, based on the dot product between the sun direction and the direction in which the sky is sampled. Finally, I enabled some simple post processing. I render the scene in high dynamic range using a 32 bit per channel float buffer for the target image, brought back to standard range using tone mapping. I also apply bloom using Godot’s world environment node.

Conclusion

Overall, I am quite happy with the progress of this project. And I think the approach thus far effectively achieves my interactive voxel world idea. I also think it has a lot of potential for future work, such as global illumination, more realistic water simulation, transparency rendering and much more. For now, I have made the code open source under the MIT license once again. Please check it out in the description if you would like to play around with it.