Population of a Large-Scale Terrain

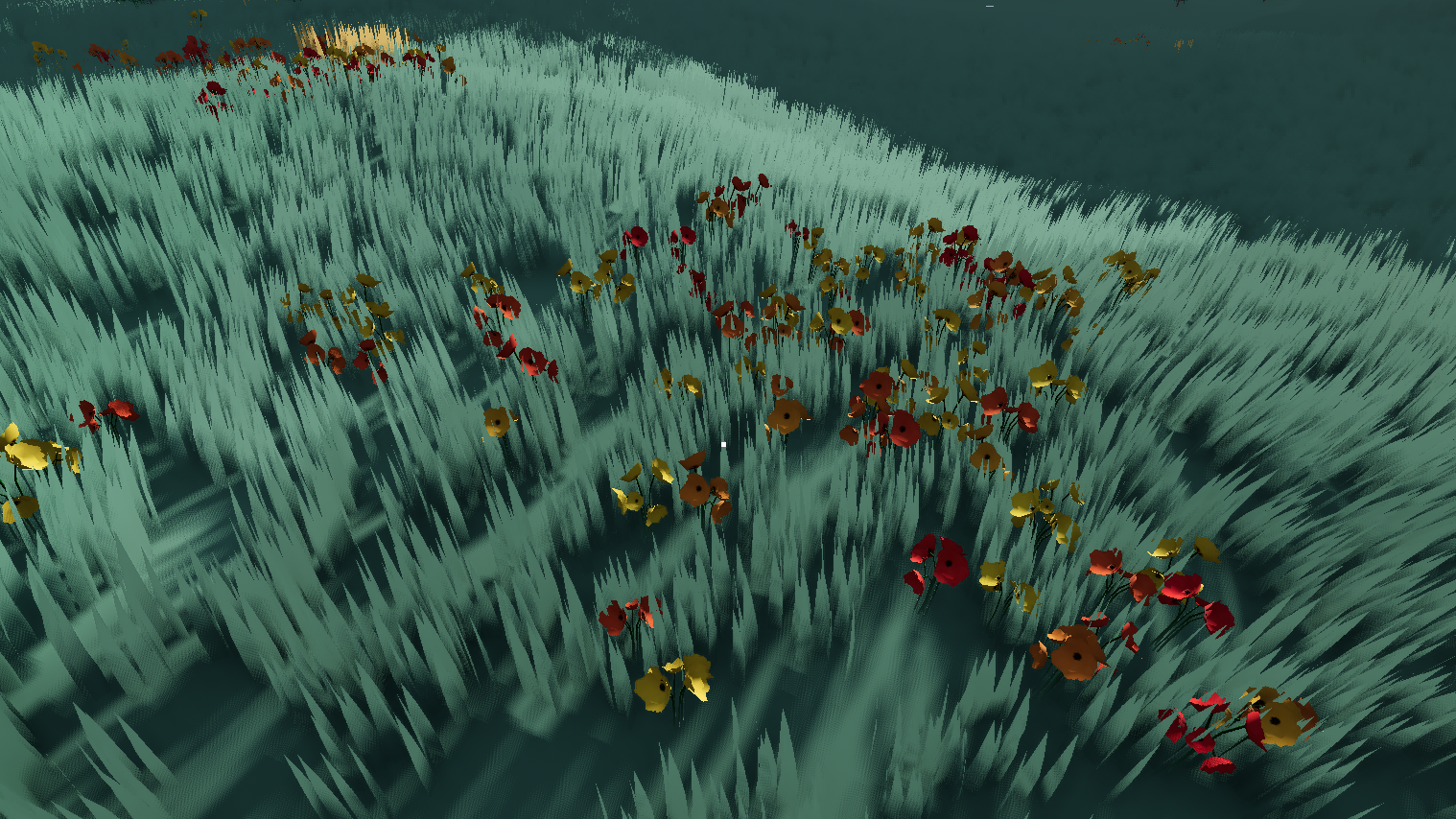

Previously I introduced a Large-Scale Smooth Voxel Terrain While impressive in scale, it lacked visual variety and complexity. One way to mitigate this is by introducing natural objects such as grass and trees.

Many voxel engines and games such as minecraft tackle this by incorporating these features into voxels too, but this can both make asset creation more difficult, and increase the demands put on our voxel octree. Instead, I chose to implement more traditional methods of distributing objects on the terrain surface, often seen in games in combination with heightmap terrains.

More precisely, I aim to populate the terrain quickly with many small objects such as grass that can be seen up close, and many large objects such as trees that can be seen from afar. I call these two distinct groups details and features respectively.

Both types of populators should support similar generation rules, such as only placing them within a certain height range, and aligning them to the normal of the terrain. They also should be affected by modifications to the terrain. However, both details and features require fundamentally different implementations to meet my demands.

Detail Generation:

We only care about details if they are close to the camera. We also don’t mind if the exact positions of details change if we move far away and come back, as no one will remember the exact positions of grass blades.

To generate the details, we iterate through all triangles of chunk meshes with a high level of detail. For each triangle, we can sample a random point using the following formula:

$$ p = v_1 + a(v_2 - v_1) + b(v_3 - v_1)$$

given that:

$$a + b <= 1$$

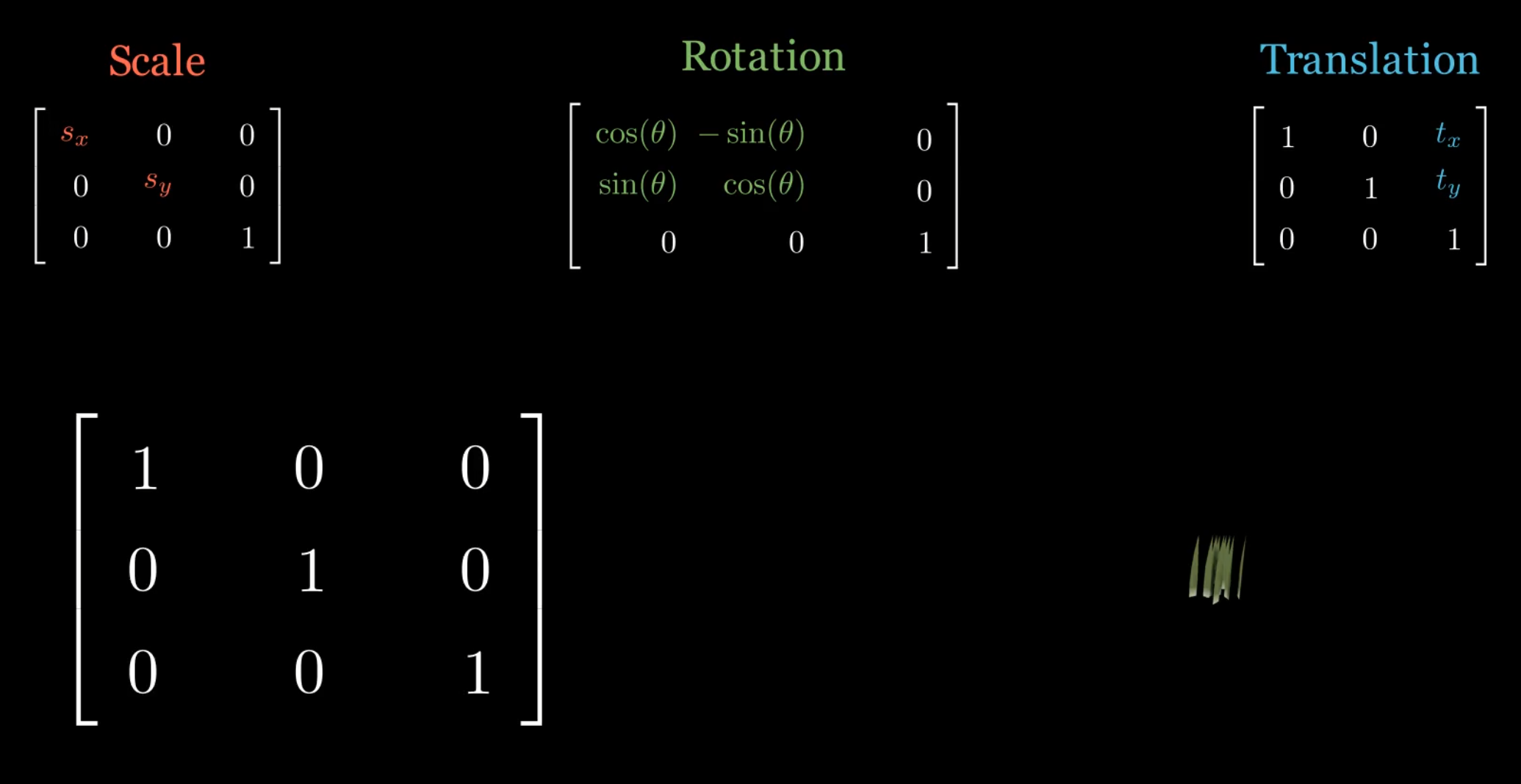

Similarly, we can sample the interpolated normal of the terrain mesh at that position, which we can use to orient the detail perpendicular to the terrain surface. We might also want to delete unwanted details here, to ensure they are not generated on a modified terrain surface for instance. We combine spatial information into a single affine transformation matrix per detail instance. These matrices can describe scaling, rotation, and translation all at once. By multiplying them in the correct order, we can transform objects however we want.

We don’t want to render each detail with a unique draw call. Instead, we use instanced rendering. The cpu sends a single draw call to the gpu with the relevant buffers and an instance count N. In turn the GPU renders N instances as fast as possible, without having to wait for the CPU to send another draw call. We can provide a buffer with N transformation matrices, and use the instance id to ensure that each instance is placed correctly.

Feature Generation:

The feature logic is a little more involved. First, remember that we want to see features from afar, and they should be persistent. This means we cannot rely on the underlying terrain mesh to place the features, as the resolution of the terrain changes with distance to the camera. Secondly, we want to remove features when the terrain is modified. Iterating through all features to check which are in range of the modification can be slow.

To solve these problems, I decided to create a secondary octree. Like the terrain, it subdivides more if nodes are both close to the camera and close to the terrain SDF. In this octree the minimum size leaf nodes are about the size of a single terrain chunk, and features are only created within these leaves.

When placing features, we want to minimize them overlapping with each other. I solve this by sampling points on the top face of the axis aligned bounding box of a leaf, using poisson disc sampling. We then raymarch through the terrainSDF to find the closest exact position of the surface below the previously sampled positions. If the found surface position is not within the leaf’s bounds, we discard it. We generate a transform matrix just like we did with details, but the normal is based on the gradient of the SDF at the surface position.

We want to control the spatial frequency of individual features. For instance, we want a small tree to show up more often than a large tree. We select what feature to generate using the alias method, which allows us to sample a discrete distribution in constant time. We initialize the weights using the feature’s user set densities, and normalize them.

To group features together, I currently use a simple 2d fractal noise function as a mask. If the noise value at a position is below a certain threshold, I do not place a feature or detail here. This check is done after generating the points, as this means the density setting on a feature is the density in areas it actually populates, which is more intuitive than the overall density.

After all this, we end up with an octree with leaves that store a list of transformation feature pairs. This means we can efficiently find and remove features in the bounds of a modified region. Moreover, we can update the octree if we move the camera, just like the terrain. If some leaf’s LoD goes under a threshold, we can temporarily remove all of the nodes representing the transforms in this node from the scenetree. This saves time, as the render engine has to consider fewer objects to render, which is more efficient than culling them after a certain distance from the camera.

Biome Rendering and Generation

As a bonus, I decided to implement a simple biome system. Currently it serves as a shallow group of features and details combined with a grass color. I decided to use some noise functions to represent some vague climate characteristics, such as temperature and humidity, similar to minecraft. We then create a predefined function that takes a sample and returns a suitable biome.

The CPU uses the noise functions directly to decide what features and details to place where. However, this would be inefficient on the GPU. Instead I generate two kinds of texture maps on the fly. First, I infrequently generate a 128 by 128 texture by sampling the noise functions around the player, which I call global biome map. This texture is used by all details and features, and it is accessed using godot’s shader globals. I use this texture to color the grass for instance. Secondly, to prevent obvious banding outside the texture bounds, I create a small eight by eight texture per chunk to sample from instead. This approach will introduce seams between chunks, but at low frequency biome noise this is not an issue.

Creating Assets

To top it off, I decided to create some decent looking 3d assets. First, I modeled some trees and flowers in Blender, and I used Krita to create textures. Then I brought everything to life using shaders. Certain effects such as wind should only apply to the parts of meshes further away from the ground, so I created a simple blender plugin to easily set vertex colors in a vertical gradient.

I also created a lower level of detail for all the trees, and I generated imposters using an existing godot plugin. They don’t look perfect currently, but they do a good job of keeping rendering performance very high.

Overall I believe to have succeeded in creating a set of algorithms to efficiently populate my terrain at a large scale. In combination with the biomes system, it effectively adds a lot of visual variety and complexity to the scene. I am currently working on some small complementary systems for this project, such as a map and interactive details, and I am also planning some larger systems I can’t wait to share more details on.