Simulating Digital Evolution

Many problems are difficult to solve using classic algorithms. This is where state of the art artificial intelligence techniques come into play. While everyone talks about large language models and diffusers nowadays, I think a different branch called evolutionary algorithms is much more interesting. Originally inspired by biological evolution, this branch of artificial intelligence aims to solve problems using elegant concepts.

While many types of evolutionary algorithms exist, they almost all share the notion of using a population to converge to an optimal solution. These algorithms are mostly designed to operate in black-box scenarios. This means that they work on any kind of problem with a fitness function that takes a valid state of a problem, and returns a score that indicates performance.

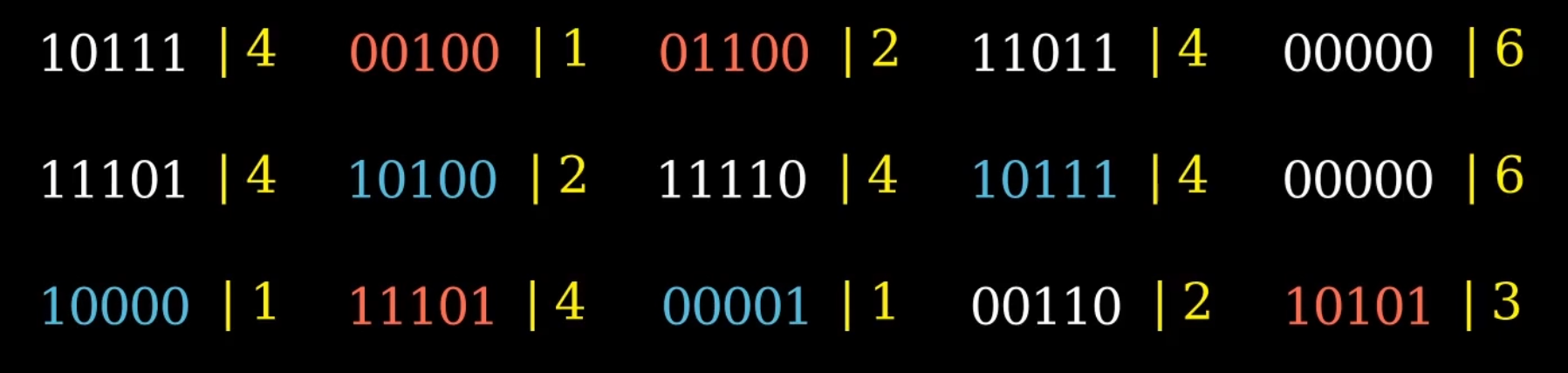

Each individual in the population is represented using a genome that represents a valid solution to the problem. Instead of DNA, we use a sequence of primitive data types, such as bits or floats. Instead of using an EA, You could imagine trying to solve this naively using trial and error, but that is like finding a needle in a hyperdimensional haystack. EAs aim to search the space of possible solutions as efficiently as possible, without relying on any problem specific heuristics.

For today, I will only consider fitness functions where higher values are better. I will also discuss two distinct algorithm classes, genetic algorithms and evolutionary strategies.

Genetic Algoritm (GA)

Out of all evolutionary algorithms, the genetic algorithm is arguably the closest to original biological evolution. First, we initialize the population with N individuals.

Then, while we are not satisfied with our solutionset, we select the best individuals, and let them create offspring by applying some form of crossover, and applying random mutations to the resulting offspring, and repeat.

Selection is often handled using tournaments. For every parent candidate, we select a small number of individuals, and pick the best. If the tournament size is large, selection pressure is high, meaning that the best individual in the population will quickly dominate the genepool.

Once two parents have been selected, we can perform crossover to create new offspring. The idea is to take two parents, and swap out genes in the genome. This can be done uniformly, or using one point crossover for example. Each crossover operation produces two offspring per two parents. We can also decide to randomly mutate the offspring, by randomly altering a random small amount of genes.

Finally, I decided to add the notion of elitism. It ensures that the best individuals are carried over to the next generation. Without it, the best solution may become lost.

Simple Benchmark

For a simple benchmark, let’s test it on a trivial binary problem. The fitness function is defined as the sum of the genome values. In our case, the genome size is 1000, population size is 100, and I used the settings shown on screen. We would expect it to find the maximal attainable fitness of 1000, but unfortunately it seems to struggle to climb after around 800.

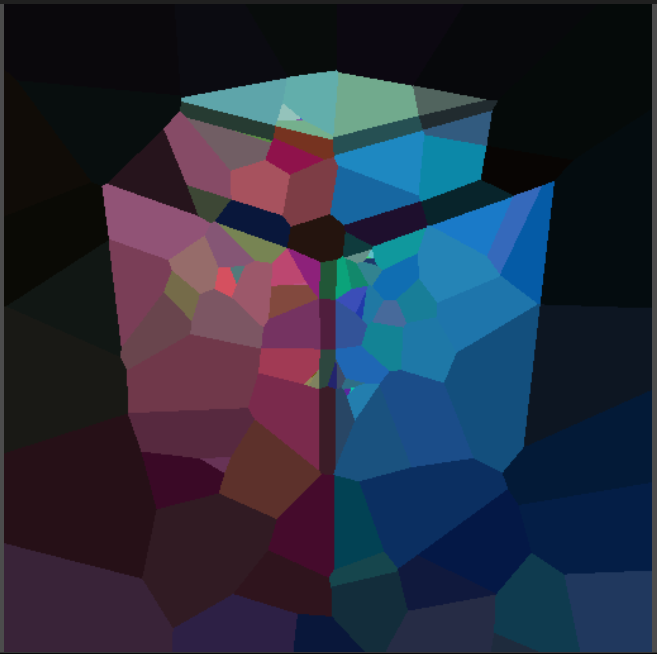

Voronoi rendering

A more interesting challenge is trying to fit a Voronoi diagram to an existing image. A Voronoi diagram is defined by a set of points with colors, where pixels in the resulting image are colored based on the color of the closest point. The idea is that we want to find a set of points and colors such that the result looks similar to the original image. We can describe the fitness as the negative sum of the squared distance between each pixel in the generated image, and the color at the same position in the original image. Because we take the squared distance between colors, larger differences are weighted extra negatively. In machine learning terms this is often referred to as an L2 loss function.

To speed up computation time, the rendering and error computation is handled by a compute shader. I use a single atomic float to accumulate the error.

Sep-CMA-ES

The classic GA is a bit slow, and struggles to come close to an acceptable solution. This likely is because it is originally designed to work on binary strings, not on floating point numbers.

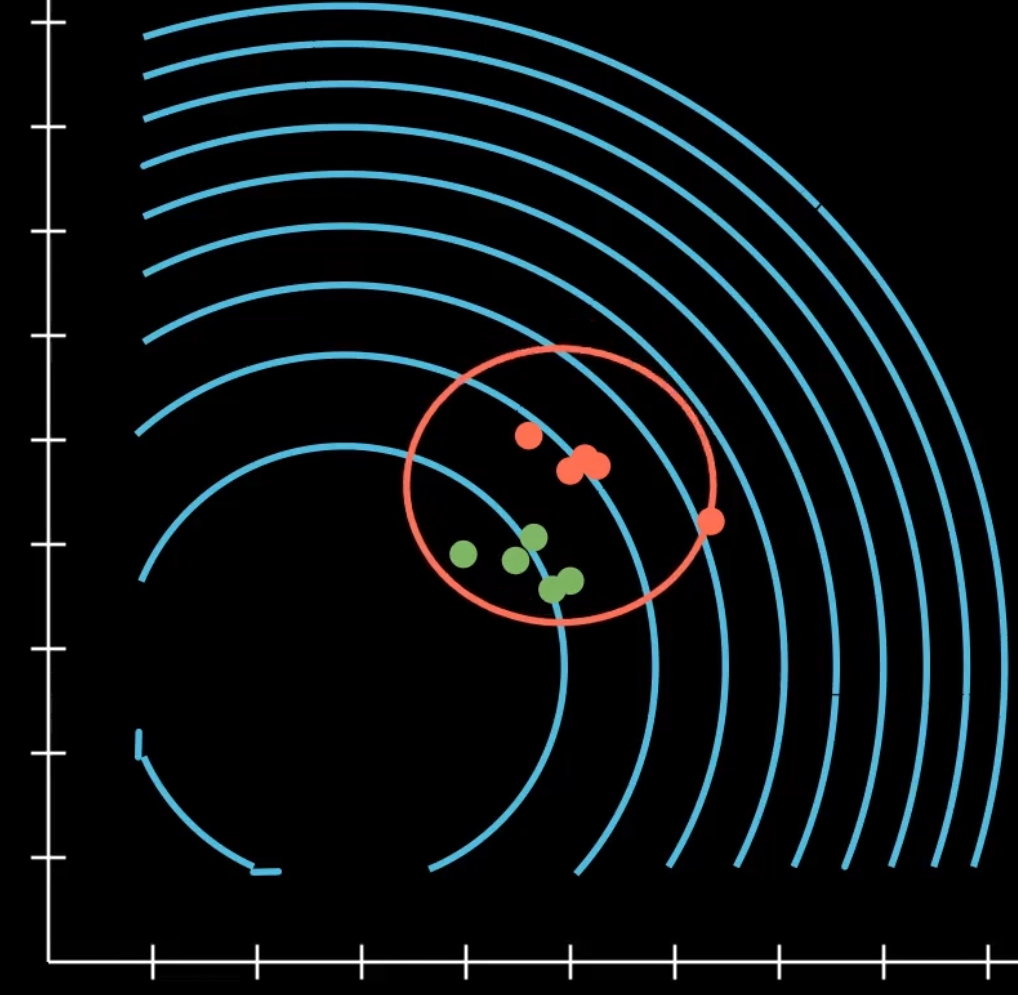

Luckily, there has been quite a bit of research in genetic algorithms. One interesting technique is Covariance matrix adaptation evolution strategy (CMA-ES). It’s a type of evolutionary strategy, where the core idea is that instead of a population, we have an N dimensional gaussian distribution we evolve over time. Every generation, we sample a new population as points within the distribution, and we reshape the distribution around individuals that were evaluated with higher fitness. By doing this over and over again, we end up with a distribution that is centered on a solid solution of the function.

Compared to GA, I believe this approach is better able to balance exploitation and exploration by essentially implicitly computing the gradients in the search space, and sampling towards promising directions.

In CMA-ES, it has a full covariance matrix. This means, we can both scale and rotate the gaussian in any way we want. This does require an N by N matrix. As N equals the genome length, large genomes can severely impact the performance of this method. Luckily, it turns out that merely using the separable or diagonal covariance matrix works well enough for this algorithm. This implies we can only scale the distribution along the basis vectors of the R^N space, but it makes the algorithm operate in linear space and time.

Conclusion